Comprised of Fail

A few days ago on Twitter, John McIntyre wrote, “A reporter has used ‘comprises’ correctly. I feel giddy.” And a couple of weeks ago, Nancy Friedman tweeted, “Just read ‘is comprised of’ in a university’s annual report. I give up.” I’ve heard editors confess that they can never remember how to use comprise correctly and always have to look it up. And recently I spotted a really bizarre use in Wired, complete with a subject-verb agreement problem: “It is in fact a Meson (which comprise of a quark and an anti-quark). “So what’s wrong with this word that makes it so hard to get right?

I did a project on “comprised of” for my class last semester on historical changes in American English, and even though I knew it was becoming increasingly common even in edited writing, I was still surprised to see the numbers. For those unfamiliar with the rule, it’s actually pretty simple: the whole comprises the parts, and the parts compose the whole. This makes the two words reciprocal antonyms, meaning that they describe opposite sides of a relationship, like buy/sell or teach/learn. Another way to look at it is that comprise essentially means “to be composed of,” while “compose” means “to be comprised in” (note: in, not of). But increasingly, comprise is being used not as an antonym for compose, but as a synonym.

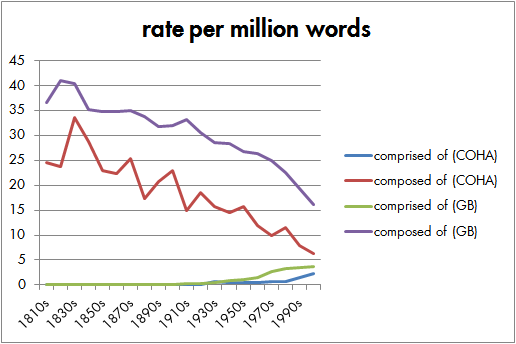

It’s not hard to see why it’s happened. They’re extremely similar in sound, and each is equivalent to the passive form of the other. When “comprises” means the same thing as “is composed of,” it’s almost inevitable that some people are going to conflate the two and produce “is comprised of.” According to the rule, any instance of “comprised of” is an error that should probably be replaced with “composed of.” Regardless of the rule, this usage has risen sharply in recent decades, though it’s still dwarfed by “composed of.” (Though “composed of” appears to be in serious decline. I have no idea why). The following chart shows its frequency in COHA and the Google Books Corpus.

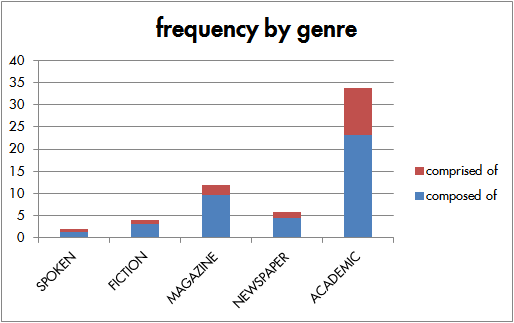

Though it still looks pretty small on the chart, “comprised of” now occurs anywhere from 21 percent as often as “composed of” (in magazines) to a whopping 63 percent as often (in speech) according to COCA. (It’s worth noting, of course, that the speech genre in COCA is composed of a lot of news and radio show transcripts, so even though it’s unscripted, it’s not exactly reflective of typical speech.)

What I find most striking about this graph is the frequency of “comprised of” in academic writing. It is often held that standard English is the variety of English used by the educated elite, especially in writing. In this case, though, academics are leading the charge in the spread of a nonstandard usage. Like it or not, it’s becoming increasingly more common, and the prestige lent to it by its academic feel is certainly a factor.

But it’s not just “comprised of” that’s the problem; remember that the whole comprises the parts, which means that comprise should be used with singular subjects and plural objects (or multiple subjects with multiple respective objects, as in The fifty states comprise some 3,143 counties; each individual state comprises many counties). So according to the rule, not only is The United States is comprised of fifty states an error, but so is The fifty states comprise the United States.

It can start to get fuzzy, though, when either the subject or the object is a mass or collective noun, as in “youngsters comprise 17% of the continent’s workforce,” to take an example from Mark Davies’ COCA. This kind of error may be harder to catch, because the relationship between parts and whole is a little more abstract.

And with all the data above, it’s important to remember that we’re seeing things that have made it into print. As I said above, many editors have to look up the rule every time they encounter a form of “comprise” in print, meaning that they’re more liable to make mistakes. It’s possible that many more editors don’t even know that there is a rule, and so they read past it without a second thought.

Personally, I gave up on the rule a few years ago when one day it struck me that I couldn’t recall the last time I’d seen it used correctly in my editing. It’s never truly ambiguous (though if you can find an ambiguous example that doesn’t require willful misreading, please share), and it’s safe to assume that if nearly all of our authors who use comprise do so incorrectly, then most of our readers probably won’t notice, because they think that’s the correct usage.

And who’s to say it isn’t correct now? When it’s used so frequently, especially by highly literate and highly educated writers and speakers, I think you have to recognize that the rule has changed. To insist that it’s always an error, no matter how many people use it, is to deny the facts of usage. Good usage has to have some basis in reality; it can’t be grounded only in the ipse dixits of self-styled usage authorities.

And of course, it’s worth noting that the “traditional” meaning of comprise is really just one in a long series of loosely related meanings the word has had since it was first borrowed into English from French in the 1400s, including “to seize,” “to perceive or comprehend,” “to bring together,” and “to hold.” Perhaps the new meaning of “compose” (which in reality is over two hundred years old at this point) is just another step in the evolution of the word.

mohinder bhatnagar

Doesn’t the devil lie in the direct and indirect narrations: Fifty states comprise the United States but The United States is comprised of fifty states?

Jonathon

I’m not sure what you mean by the “direct and indirect narrations,” but both of those examples are wrong according to the traditional rule. Following the rule, you’d say that the fifty states are comprised in the United States and that the United States comprises fifty states. But the weird thing is that it’s perfectly clear either way, which is probably why this usage is so widespread.

What’s the deal with “compose” and “comprise”? « Motivated Grammar

[…] more on these words, check out Arrant Pedantry and Language Log's takes, which talk more about the passive forms than I […]

Pete

I might be a bit late to the party as this post is nearly a year old. But it’s interesting to note that this is just one of many reciprocal antonyms that are often confused. Other examples are “borrow”/”lend”, “learn”/”teach” and “scratch”/”itch”.

What makes “compose”/”comprise” different from these other pairs is that they’re learned words, so the confusion is found not just in everyday speech but even in edited prose.

Jonathon

Good point, Pete. The use of “learn” to mean both “learn” and “teach” comes from the merger of “learn” with the related word “lere”, which meant “teach”, but I think the others are simply extensions of one word into the other’s semantic space.

But those others are all highly nonstandard. As you say, “comprise” is the only one found in edited prose.

Mike

Meta-pedantry: I noticed the article states, “They’ve extremely similar in sound, …”

Is that a construct I’m not familiar with, or an error?

Jonathon Owen

Seriously? What do you think it is?

I don’t guarantee typo-free posts, and I certainly welcome corrections, but there’s no need to be snide.

jbinsb

Nice treatment of the topic. I realize that the usage is changing, but I will continue to use it traditionally (two different, though similar-sounding, words to signify different things) and to edit it out of text I encounter that has it wrong.

Given that you know you’ll attract nerds of the wordsmithing variety to this blog and that I know I am one, I can’t resist noting that “increasingly more common” is redundant, but you know that, and this is a blog and not every oversight will get cleaned up. Cheers.

Arun

Dear Jonathon, should we ignore proper usage just because of some misinformed souls. Many people do not know the difference between ‘affect’ and ‘effect’ or ‘its’ and ‘it’s’. Similarly, in South Asia, ‘revert’ has become a synonym of ‘reply’ and ‘prepone’ an antonym of ‘postpone’. I believe rules should not be broken because of ignorance masquerading as popular or common usage.

Jonathon Owen

The real question is, who decides what’s proper? Who makes these rules, and how do they have any authority or efficacy separate from popular or common usage?

Mark

Nice article. To respond to Arun, I share the frustration for the practice of building language out of misuse. But I’m also aware that the English language is rife with examples of that kind of mutation. (Ex. supposably and thusly) And there are many more whose meanings were solidified so long ago few know they’re born from ignorance. I think jbinsb’s approach is a good one. Correct it where you have influence. For good and ill, there’s no absolute authority over proper English. So we need to make our votes count.

Mike Treanor

I have always viewed this confusion as one symptom of a broader degeneration of English grammar: people are increasingly avoiding any knowledge of the parts of speech. It is just too much work to think about that stuff. Transitive and intransitive verbs now, subjects and objects soon. This is being spurred along by marketing (which began with “cigarettes tastes good like a cigarette should” and “to boldly go where…” and by news appearing on web pages rather than in print, where correct English apparently adds no credibility to a story and being first means everything. The language no longer supports the expression of finer points, and I believe we will eventually lose the ability to appreciate them.

Ten Most Common Errors Made by Writers: #1 | Polishing Your Prose

[…] not alone in this seeing this. Jonathon Owen, in his blog Arrant Pedantry, cited this example from Wired […]