The Atlantic Is Wrong about Dog Pants

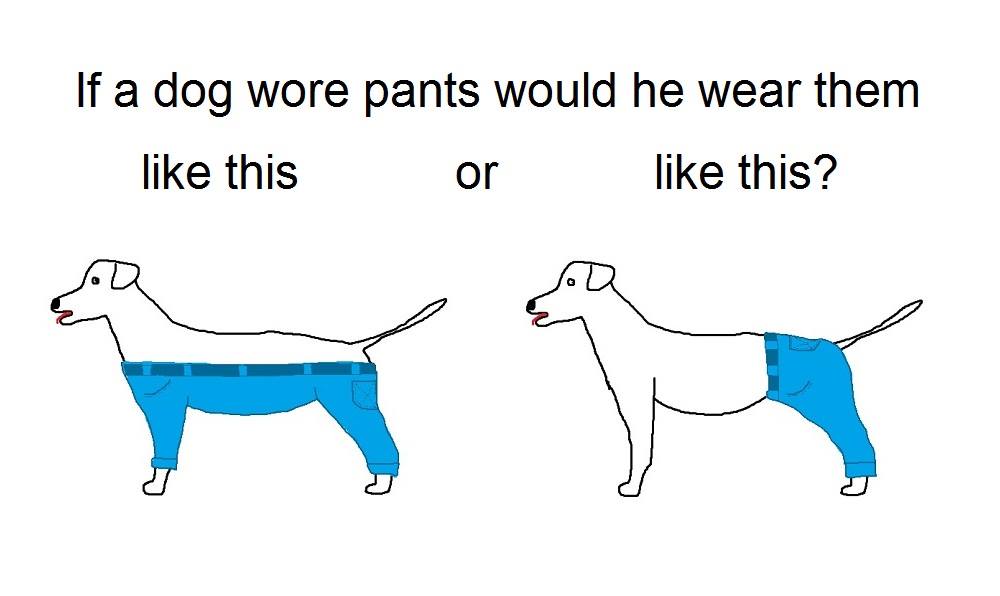

While on my Christmas vacation, I came across this article in the Atlantic on the question of what proper dog pants should look like: the image on the left, or the image on the right.

The image originally came from a Facebook page called Utopian Raspberry—Modern Oasis Machine (UR-MOM), and from there it hit Twitter and various other sites. One Twitter poll found that over 80 percent of respondents favored the two-legged version.

But Robinson Meyer at the Atlantic insisted that these people were all wrong, and he’d prove it with linguistics. This is certainly a laudable goal, but his argument quickly goes off the rails. After insisting that “words mean things”, as if that were in dispute, Meyer asserts that pants cover all your legs. Humans have two legs, so our pants have two legs. Dogs have four legs, so dog pants should have four legs. QED. What’s left to discuss?

Well, a lot. Even though it’s clear that words mean things, it’s a lot less clear what words mean and how we know what they mean. Semantics is a notoriously tricky field, and there are a lot of competing theories of semantics, each with its own set of problems. There are truth-conditional theories, conceptual theories, Platonist theories, structuralist theories, and more.

But rather than get bogged down in theoretical approaches to semantics (which, frankly, were never my strong suit), let’s take a more practical approach to answering that fundamental question What are pants? by thinking about what features make something pants or not pants. We’ll ignore the question of dog pants in particular for the moment and focus on people pants.

Meyer says that pants cover all your legs, but we could also say that pants cover both your legs or maybe just that they cover your two hind limbs, and we would still wind up at the same place—two-legged pants. It’s not obviously true that pants must cover all your legs. In fact, it’s rather strange to say that pants cover all your legs, because that phrasing seems to assume that you might have more than two. You’d only phrase the definition this way if you anticipated that it might have to cover four-legged dog pants, which is begging the question. The more parsimonious definition would say that you only have to cover both legs.

Meyer’s definition is also missing one important part: the butt. Pants don’t just cover your legs—they cover your body from the waist down. Depending on where they stop, you might call them shorts, Capris, pedal pushers, or just pants. But if they don’t cover your butt, they’re not pants—they’re hose or leggings or some such, though nowadays these usually go up to the waist too. (I’m using the term waist a little loosely, since it’s technically the point halfway between the hips and the ribs, and most pants sit somewhere around the hips.) So at least when it comes to humans, pants cover most or all of the pelvic area plus at least some of the legs.

Note that underpants don’t necessarily cover any of the legs, and some shorts cover barely any of the legs at all. So if you want a definition that covers underwear too, covering the butt is actually more crucial than covering the legs. Even if we assume for the sake of discussion that we’re not including underwear, simply covering the legs is not sufficient. And covering all legs, regardless of number, is obviously not necessary. We could even say that pants cover the lower or rear part of the body, starting at the hips and ending somewhere below the butt, with separate parts for each leg (to differentiate pants from skirts or dresses).

Now let’s move on to dog pants. As far as I know, the word waist isn’t usually applied to animals other than humans, though dogs still have hips and ribs. So applying the minimum definition of covering the pelvic region and at least part of the two hind limbs, the correct version is clearly the one on the right. Strangely, Meyer says that we already have a term for the image on the right, and it’s shorts, because shorts cover only some of your legs. But this is playing really fast and loose with the definition of some. Shorts cover some part of each leg, not all of some leg. And anyway, shorts are simply a subset of pants, so if the image on the right is shorts, then it’s also pants.

The one on the left covers not just the legs but also the entire ventral side of the torso, which pants don’t normally do. Even overalls cover only part of the front of the torso, and they don’t cover the forelimbs. The closest term we have for something like the image on the left is jumpsuit, but it’s a backless, buttless jumpsuit. The image on the left makes sense as pants only if you’re fixated on covering all legs rather than just two and don’t mind omitting necessary feature of pants while adding some unnecessary features. Not only that, it’s not a very practical garment—as Jay Hathaway at New York Magazine points out, it wouldn’t even stay up unless you have some sort of suspenders going side to side over the back.

And this points out the real flaw in Meyer’s argument. He says that humans wear two-legged pants because we have two legs, but this isn’t really true. We probably wouldn’t wear four-legged pants if we had four legs, because it doesn’t make sense to design an article of clothing like that. Consider the fact that we don’t design clothes differently for babies just because they crawl on all fours.

Pants have nothing to do with which limbs we stand on and everything to do with how we’re shaped. We wear one article of clothing to cover the top halves of our bodies and another to cover the bottom halves because it’s easy to pull one article over the top and one over the bottom. Dogs aren’t shaped that differently from us, so when we make clothes for dogs, we make them the same way. Pants just happen to cover two legs on people because our two hind limbs just happen to be legs.

Besides, the whole question is moot because dog pants already exist, and they’re of the two-legged variety. What should we call them if not pants? Insisting that they’re not pants comes as a result of getting hung up on a supposed technical definition and then clinging to that technical definition in the face of all good sense.

And consider this: if dog pants have four legs and no back or butt, what would a dog shirt look like?

Dan McCelllan

“Words mean things” = “I don’t understand how language works.”

Jonathon Owen

Ha!

Mike

Seems like a sound analysis. No one, of course, seems to made inquiries among actual dogs, ha.

As an irrelevant aside, I got sidetracked into wondering about “semantics ARE not my strong suit” vs a possible (?) “semantics IS not …”. It feels like I can mentally flip between them, and both can sound right, but it requires rethinking the subject on each flip. As I say, irrelevant.

Jonathon Owen

Semantics is one of those words that Merriam-Webster says is singular or plural in construction. Sometimes I flip back and forth and can’t tell which I like better.

But in this case, I think I actually had in mind that “theoretical approaches . . . were never my strong suit”.

Terry Collmann

Them’s not pantz annyways. Thems is traaahziz.

Josh

The Canadian company that makes a dog outfit like the left drawing avoids the issue on their website by only calling them by their own made up name, Muddy Mutts.

Chad Nilep

Couple of things:

First, I’m curious about your use of ‘hind’ in “they cover your two hind limbs” et seq. If one accepts that humans stand erect, neither set of limbs is really ‘hind’ (at the back) in the way quadruped legs are.

More to the point, I think a prototype-based inquiry may help. You’ve mentioned underpants, stockings, jumpsuits, and skirts as things that may or may not be pants. I would add those trousers with one leg cut off that people sometimes wear when a leg is in a cast, and maybe the “onesies” worn by babies. By considering these and other items, we might be able to arrive at an understanding of bad pants and better pants. Any road, I think we come to the same destination: the butt is at least as critical as the legs in defining ‘pants’.

Jonathon Owen

I used the term “hind” because I wanted something that referred to its position relative to the torso; that is, I wanted something that would cover both a dog’s hind legs and a human’s legs. I’m not sure if that’s the correct anatomical term.

I thought about taking a prototype-based approach, but by that point I was already several hundred words in and didn’t want to make it too much longer. But I agree that it would have arrived at the same destination.

Elizabeth d’Anjou

Shout-out of appreciation from a one-time high-school debating champion for the lovely old-school use of “begging the question.”

Mark Schultz

I am panting after all that heavy lifting! Thanks for the exercise and clarification. Nobody like a semanticist to muddy the water when common sense is called for.

Andy Hollandbeck

Sound and well-reasoned. Which academic journals have you submitted this to so far?

Jonathon Owen

The Journal of Semantics, The Journal of Canine Studies, and The Journal of Applied Trouser Sciences. No responses so far, sadly.

Kevin

Pants is Short for pantaloons. There has been a lot of discussion about pants, shouldn’t we now consider the loons too?

Intchanter / Daniel Fackrell

Hey Johnathon! LinkedIn told me you were getting noticed in the media (which I guess, by their definition, is another blog), which let me find your blog here.

I find this post excellently well reasoned, and will browse around to see what other wonderful things you have here.

Jonathon Owen

Thanks, and good to see you, Daniel! And yeah, I don’t know why LinkedIn thought that other blog counted as news, but I’ll take it.